Early Descriptions

The first documented traces of the German Shepherd date back to the 7th century. In the Germanic code of laws, the value of a shepherd dog was estimated at 1 gold solidus, and at 3 gold solidi for a shepherd dog capable of killing a wolf.

In the 16th century, the Swiss naturalist Conrad Gessner described shepherd dogs that had to be white so that shepherds would not confuse them with wolves when, at dusk, the latter attacked the flocks.

The German Shepherd, Between Dog and Wolf

Some authors claim that in the 10th century monks from the Munster valley may have bred shepherd dogs with tamed wolves.

A new breed would have emerged, with selective breeding gradually fixing its characteristics. But everything suggests that they were not wolves, but local shepherd dogs.

In 1901 Richard Strebel, author of cynological publications, claimed to have seen Phylax von Eulau I provoke the fury of a pack of Borzois—known for their wolf-hunting talents—at a dog show in Dresden. This cast doubt on a possible crossbreeding between wolves and German Shepherds, but this reaction was certainly due only to their resemblance.

Similarly, in 1936, Captain and dog enthusiast Will Judy, in his Dog Encyclopedia, reported that in 1887 Christian Burger of Leonberg crossed wolves with his shepherd dogs to improve their physical performance. But this was an isolated experiment, with no influence on later breeding. The resemblance of the German Shepherd to the wolf therefore does not come from recent crossings between the two animals.

In the 20th century, it was widely accepted that the dog (Canis familiaris) descended from wolves, particularly the gray wolf (Canis lupus). However, recent Japanese studies suggest that today’s dog breeds may not have evolved from the gray wolf, but rather that dogs and gray wolves share a common ancestor from a now-extinct wolf species that lived thousands of years ago. The findings suggest that Canis lupus hodophilax is the closest relative of the first East Asian dogs, and perhaps even of all dogs.

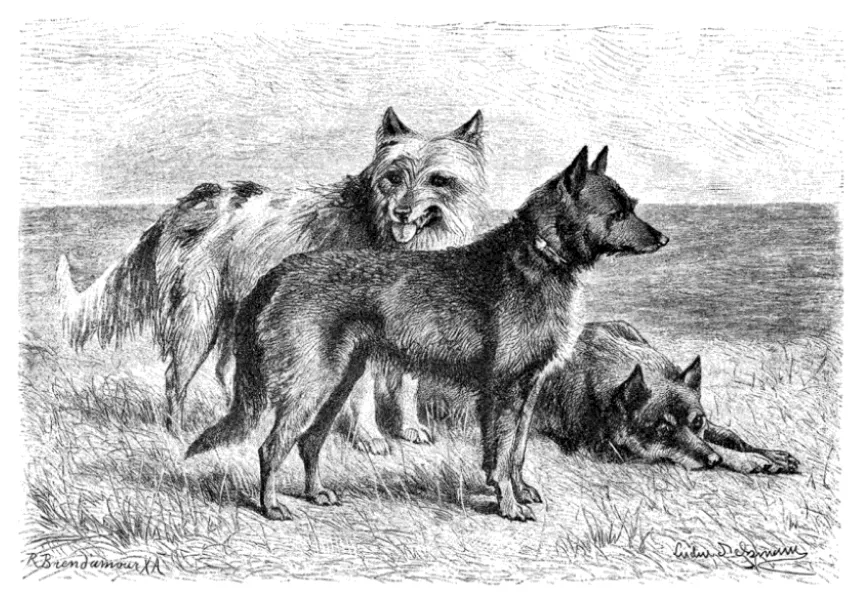

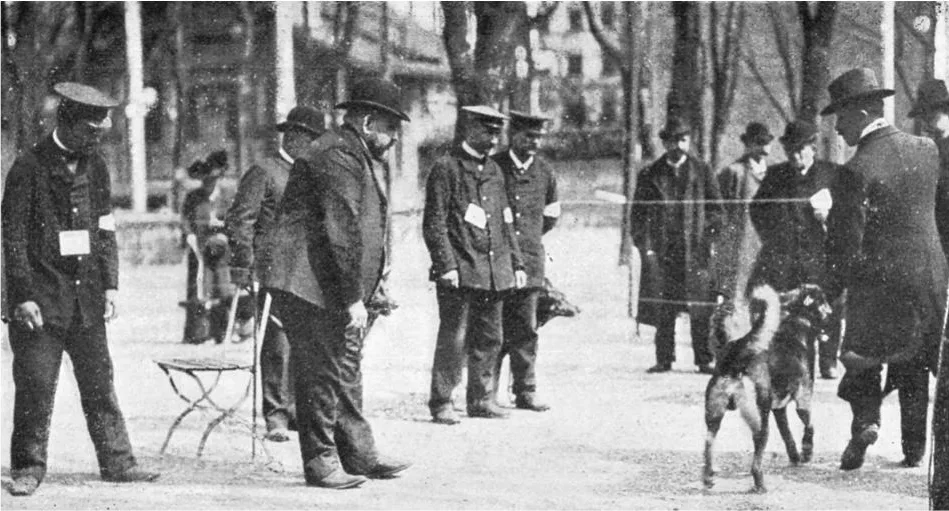

Shepherd dogs in the 19th century.

First Attempts to Standardize German Shepherd Types

In 19th-century Germany, no homogeneous breed of shepherd dog clearly stood out. Instead, there were several regional types: the Württemberg, Thuringian, Swabian, Bavarian, or Hessian shepherds.

In the 1870s, the rural crisis caused by the industrial revolution led to a decline in the number of shepherd dogs, but at the same time fostered a new appreciation for these valuable animals. The gradual disappearance of rural traditions created a cultural trend toward rediscovering rural values, which transformed the shepherd dog into a companion dog in cities.

Furthermore, since 1871, Germany—under Bismarck’s Prussian leadership—was undergoing centralization. Unlike the French, who tried to select different regional types of shepherd dogs, the Germans preferred to create a national breed, a symbol of German rigor and quality.

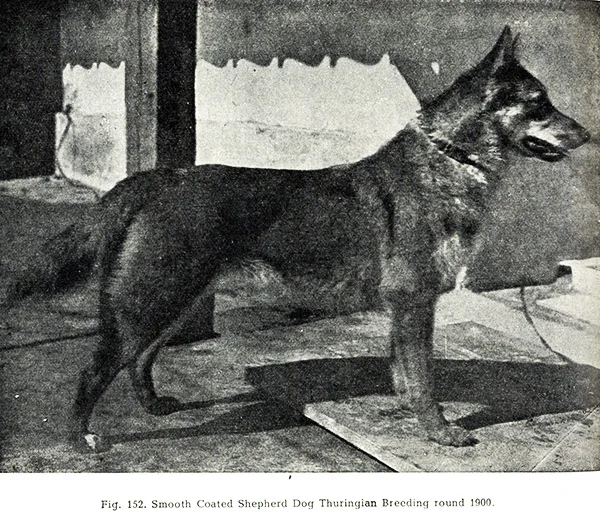

As early as 1877, some breeders made an initial selection from two types: the Thuringian Shepherd, short-haired and gray, with medium bone structure, erect ears, and valued for its speed and vigilance, making it an excellent herder; and the Württemberg Shepherd, large and strong, with dark thick fur, a powerful head, and used to protect flocks in the mountains. The offspring of these first breeding experiments were extremely heterogeneous, but commercially successful nonetheless.

Thuringian Shepherd type dog around 1900.

As early as 1878, German breeders tried to join forces to create a specific type. At his Prussian kennel "César et Minka" in Zakna, Otto Friedrich bred shepherd dogs he sold throughout Europe, which likely infused new blood into the development of local breeds in neighboring countries like Belgium.

On December 16, 1891, a group of enthusiasts, including Captain Riechelmann and Count Von Hahn, founded the first German Shepherd breeders’ club, the Phylax Society (from the Greek "guardian" or "protector"), with the goal of standardizing local shepherd dogs.

Already owning medium-sized dogs with erect ears and low-carried tails, their focus quickly shifted to aesthetics, but disagreements arose. Some members believed that physical appearance mattered little as long as the dog could perform its assigned tasks with agility and endurance. Others considered physical appearance more important, arguing that beauty or at least consistency of type should prevail over working ability. Finally, some believed both beauty and working ability were possible, refusing to settle for less. Unable to reach an agreement, the club dissolved in 1894.

However, the dream of a very particular shepherd breed did not die with the Phylax Society. A few of its members never lost sight of the goal, and one man in particular was determined to take the future of the German Shepherd into his own hands.

The Breed’s Foundation by Captain Max von Stephanitz

Captain Max Emil Friedrich von Stephanitz, born in Dresden in 1864, would become the true father of the German Shepherd thanks to his rigorous selection process, which he maintained throughout his 36 years leading the breed.

🔗 And Stephanitz Created the German Shepherd

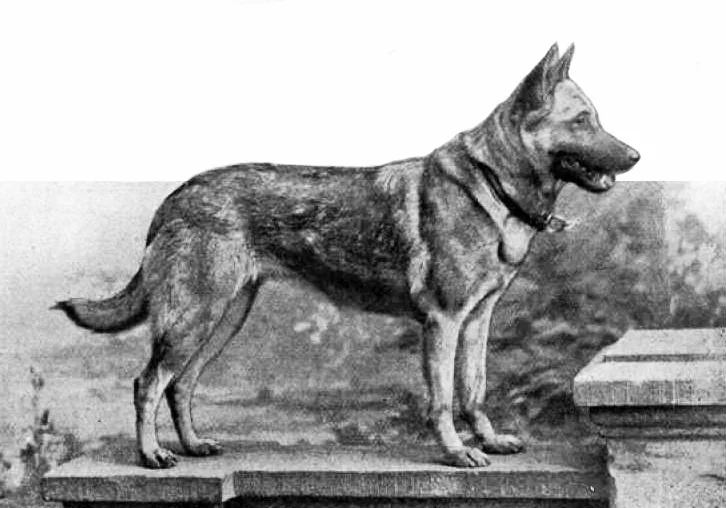

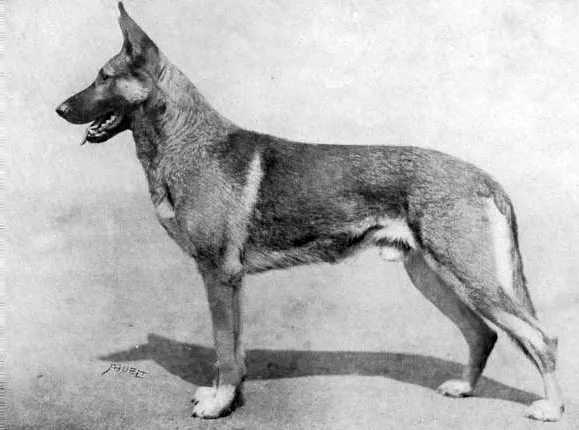

On April 3, 1899, he attended an exhibition in Frankfurt with his friend Arthur Meyer. He immediately fell in love with a young gray and yellow Thuringian herding dog, Hector Von Linkshrein, which he purchased for 200 marks, a considerable sum at the time. Renamed Horand Von Grafrath, after his Bavarian farm, he became the first dog registered in the German Shepherd studbook, the Zuchtbuch für deutsche Schäferhunde, abbreviated as SZ.

Von Stephanitz described him as follows: "Horand embodied the dearest dream of dog enthusiasts of the time. He was large, standing 60–62 cm at the withers, with powerful bone, a harmonious silhouette, and a head with a noble expression. Simple in structure, the entire dog radiated driving power. His character matched his exterior qualities: wonderful in his loyalty to his master, a gentleman’s uprightness combined with an immense zest for life. Though untrained in his youth, he obeyed his master’s slightest nod. Yet left to himself, he became the naughtiest rogue, the wildest poacher, and an incorrigible fighter. Never idle, always eager, friendly with strangers but never submissive, joyful with children and perpetually loving. His faults stemmed from upbringing, not from his lineage. He suffered from unchanneled excess energy, for he was in paradise when someone cared for him, becoming then the most obedient of dogs."

He was used as the main stud, and all his descendants are ancestors of today’s German Shepherds. He sired 53 litters with 35 different females, producing 149 registered offspring. Although this may seem limited, at that time distemper devastated many litters, resulting in a low survival rate. Furthermore, many descendants were never recorded. Horand was bred three times with his own daughters and with females descending from Polux, his grandfather—a practice common at the start of breeding, when high inbreeding was used to fix desired traits and pass them on to future generations.

His most famous offspring was Hektor von Schwaben (SZ 13), born in 1898, who sired 141 descendants from 39 females. Rumor had it that his mother, Mores von Plieningen (SZ 159), had a great-grandfather crossed with a wolf, but Von Stephanitz denied this.

Von Stephanitz placed great importance on dissociating the German Shepherd from the wolf. In his 1923 book, he devoted over a hundred pages to the dog’s origins, claiming it descended from a prehistoric dog (Canis poutiatini) whose bones had been found in Moscow, and detailing its differences from the wolf. If it could be shown that the two animals had distinct lineages, then the belief that dogs descended directly from wolves—a serious threat to breeding—could be refuted. At the time, the wolf was seen as a dangerous and unpredictable animal, capable of attacking humans unexpectedly. If the German Shepherd were thought to have wolf blood, it too could be considered dangerous. Thus, it was essential for Von Stephanitz to prove it was not.

Horand von Grafrath (SZ 1), the first German Shepherd registered in the studbook.

Max von Stephanitz wanted to establish a national shepherd type. On April 22, 1899, an architect, Hans Abesser; three sheep breeders, Friedrich Arnoldt, Friedrich Goymann, and Otto Weber; a mayor, Philipp Barth; two hoteliers, Anton Eiselen and Karl Schlenker; two industrialists, Max Feer and Charles Kammerer; a magistrate, Arnold Oehler; and the two initiators of the project, Max von Stephanitz and Arthur Meyer, founded the German Shepherd Club in Stuttgart, the Verein für deutsche Schäferhunde, abbreviated SV. Max von Stephanitz became its president. The SV quickly grew to 60 members, and the first championship was organized that same year. The first title of Sieger (Champion) was awarded to Jörg von der Krone (SZ 163), and the first title of Siegerin (Female Champion) went to Lisie von Schwenningen (SZ 30).

Lisie von Schwenningen (SZ 30)

On September 20, 1899, the first general assembly of the SV took place in Frankfurt am Main, and the first breed standard was published to establish the rules and judging criteria. Von Stephanitz insisted that all working sheepdogs be automatically admitted, establishing the principle that would guide him throughout his life: a German Shepherd should above all be a working dog. He wrote: “A German Shepherd is any shepherd dog living in Germany that, through constant exercise of its shepherding qualities, attains perfection of body and mind, evaluated solely from the standpoint of usefulness.”

According to him, the ideal German Shepherd breeder keeps only a few breeding dogs to maintain close contact with each and carefully select those that would improve the breed: “The shepherd dog must be considered as an individual. The breeder must be able to care for him, especially while the dog is still young, and this is only possible with very few dogs. Breeding in large numbers is a curse for the breeder, as it leads him astray and deprives him of real joy in breeding.” The dog’s place within the family was essential: “All the wonderful qualities of a good shepherd dog will only emerge when he stays a long time in the same hands, preferably from a young age, where, having taken his place in the home, he shares in the family’s joys and sorrows. He will be completely broken in body and spirit wherever he is treated merely as a commodity.”

In the same vein, Max von Stephanitz did not believe in keeping dogs regularly in kennels, noting that this would prevent them from performing at their best: “Whenever a dog is kept in a closed kennel, he declines not only physically but also mentally.” He emphasized the importance of early puppy education: “His education must be handled by his owner. If this education is neglected or started too late, it is not uncommon for the young animal to become half-wild through neglect or ruined by kennel life. On the other hand, overly harsh and loveless training will cause psychological distress in the growing dog, and his abilities will not develop, as the trust in his master, which is essential, will be lacking.”

“A trainer with a nervous and impatient temperament will never achieve good results. To succeed, the trainer must give clear and precise orders, work consistently, and with affectionate understanding of the animal and its nature; and finally, he must have experience. Experience cannot be gained at a study table or from a book; it only comes with practice and constant use of dogs of all ages and developmental stages. The dog obeys willingly and confidently the calm and clear-headed trainer. Genuine joy in working is the foundation of success. If the dog makes a mistake, fails to understand an exercise, or fails in obedience, the trainer must ask himself, ‘Where did I go wrong?’”

Von Stephanitz did not consider color important. In 1908 he wrote: “Our German Shepherds have never been bred for a particular color, which is a completely secondary consideration for a working dog. Claims that a specific color of German Shepherd — including white — is better than another are pure nonsense.” He added that color should not be defined in the standard but remain a breeder’s choice. The earliest German Shepherds ranged in color from black to wolf gray in all its shades and solid white. Greif von Sparwasser, the maternal grandfather of Horand von Grafrath, was a white-coated herding dog. Nevertheless, in his work von Stephanitz expressed a preference for well-defined colors that enhance the overall impression of the dog.

Max von Stephanitz encouraged owners and breeders to use the breed by promoting herding competitions. Exceptional results from Belgian shepherd dogs in police service in Belgium led the German police administration to organize similar trials. The SV made its experience, resources, and dogs available and published a brochure in November 1901 recommending the dog for defense and tracking, distributing it to all police offices in Germany, emphasizing the dog’s intelligence, strength, trainability, and tenacity. The first protection dog competitions were held in 1903, consisting of three parts: obedience, defense, and tracking.

The evolution from shepherd dog to police dog was seen as a natural and beneficial development. He wrote: “We will only maintain our robust and healthy breed, whether as amateur breeders or private owners, if we allow them to work. The SV imposed this rule: to breed a shepherd dog is to breed for work. To make this fundamental condition possible for dog lovers, particularly city dwellers unable to work their dogs with herds, the SV found other ways for the dog’s benefit through military and public service. After all, the shepherd dog, through its evolution, is particularly suited to this service, for the dog’s and the community’s benefit.”

In October 1909, the SV offered a reward of 25 marks to dog handlers for each homicide successfully solved by a German Shepherd. Over 18 months, the SV paid this sum 18 times !

Judging of German Shepherds at the Berlin exhibition organized by the SV on April 20, 1905.

The breed’s success continued: by 1912, the SV had 6,000 members. The German Shepherd quickly gained popularity in Europe, the UK, and the United States, where breed clubs emerged. France discovered the breed as well, and the CFCBA (French Club of the German Shepherd Dog) was founded around 1910 after the first exports. In the first half of 1912, 4,132 dogs arrived in France. In 1913, Georges Barais, a textile industrialist, founded the Alsace Shepherd Club, which became in 1920 the SCBA (Society of Alsace Shepherd Dogs), and then in 1922 the Society of German Shepherd Dogs.

World War I severely tested many German Shepherds, which demonstrated their exceptional value in wartime, building the breed’s legend at the cost of their lives.

Birth of the modern German Shepherd

After the war, the German Shepherd, having proven countless qualities, was in high demand. In 1919, 20 years after the creation of the breed club, 150,000 German Shepherds were registered in the pedigree book. Breeders produced them in large numbers to satisfy both domestic and foreign demand. This led to a drift from the original type, with dogs becoming taller, larger, and sometimes temperamentally unstable.

To prevent these excesses, the Körbuch (Selection Book) was created in 1922 to complement the pedigree book and preserve the character traits that originally made the breed successful. Only dogs suitable for breeding were recorded after examination by a judge. By then, the SV had over 40,000 members, an exceptional number for the time.

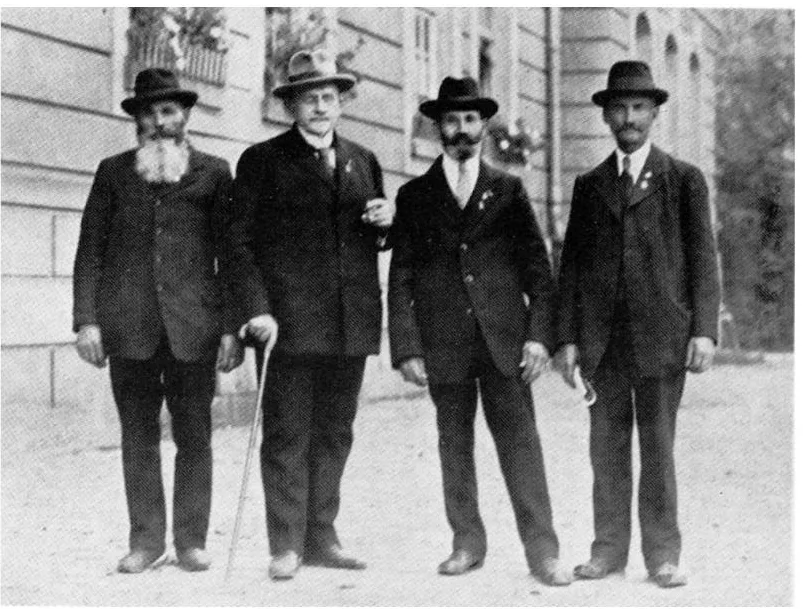

For the 25th anniversary of the German Shepherd Club in Hanover in 1924, four of the twelve founding members were present.

From left to right: Friedrich Arnoldt, Max von Stephanitz, Friedrich Goymann, Otto Weber.

Max von Stephanitz was particularly careful in selecting breeding dogs. Concerned about the growing trend toward oversized specimens, he felt the breed was heading in the wrong direction. At the 1925 championship, he awarded the title to a dog different from the previously appreciated standard, Klodo vom Boxberg. Klodo was a medium-sized, gray-and-tan dog, powerful and balanced. He impressed with his anatomical structure and graceful, elegant gait, marking a new era with less rustic dogs and modern physical harmony. Klodo vom Boxberg had already been Czechoslovak Champion in 1923.

That same year, the German Shepherd became the most popular breed in the United States, partly thanks to the heroic exploits of movie star Rin Tin Tin.

🔗Rintintin, the Heroic Dog of Cinema

Klodo vom Boxberg (SZ 135239) – Imported to the United States, he became one of the foundation dogs of today’s North American lines.

In the 1930s, several prominent Nazi Party members actively participated in the German Shepherd Club, eventually taking control. They sought to breed dogs for appearance rather than ability, contrary to von Stephanitz’s principles. Propaganda used the courage and legendary loyalty of the German Shepherd as symbols of National Socialism; Hitler’s dog, Blondi, appeared in official photos and was killed on the eve of his suicide.

🔗Blondi, a dog in the service of Nazi propaganda

White German Shepherds continued to appear due to a recessive gene. Nazis falsely claimed they suffered health issues like deafness, blindness, and mental instability, deeming them undesirable. White puppies were banned from breeding and exhibition and euthanized at birth. Worldwide, some breeders continued producing white German Shepherds, particularly in the US and Canada.

Nazis controlled breeding and appointed unqualified inspectors who sometimes seized kennels. Dogs not meeting the regime’s ideal were often killed on the spot.

Max von Stephanitz resisted the Nazi government’s plan to merge the SV into a general domestic animal organization. Threatened for defying Nazi directives, he resigned in 1935 from the club he had founded 36 years earlier. He died the following year at 71, shortly after the death of his favorite dog, Egga, leaving a 776-page work on the German Shepherd, Der deutsche Schäferhund in Wort und Bild. He wrote: “Make an effort for me: ensure my shepherd dog remains a working dog, for I fought my whole life to achieve this goal.”

Dr. Kurt Roesebeck, an SV member since 1904, succeeded him at von Stephanitz’s request. He had authored several scientific works on the German Shepherd and was internationally renowned.

In 1930, at the Morris & Essex Dog Show on Geraldine Rockefeller Dodge’s estate, von Stephanitz was invited to judge, drawing large crowds of breed enthusiasts.

World War II slowed breeding, as many owners served in the army, which requisitioned the best dogs, reducing the breeding stock. In the war’s final phases, many valuable breeding dogs were lost.

In April 1946, Caspar Katzmair, an SV member since 1936, became president after Roesebeck’s resignation. The US authorities asked him to reorganize SV activities. He appointed a president for each of the four Allied powers occupying Germany, who worked under his supervision to rebuild the breed. Exhibitions, suspended since 1943, resumed the same year. Despite postwar difficulties, the breed’s popularity grew rapidly in Germany, with SZ registrations rising from 3,000 in 1945 to 51,000 in 1949. Few dogs were exported during this time, as Germany focused on rebuilding its stock.

The division of Germany in 1949 into the GDR and FRG led to the creation of East German lines, DDR (Deutsche Demokratische Republik). The East German government controlled German Shepherd breeding as a military dog, enforcing strict guidelines to produce strong, enduring, robust dogs resistant to extreme physical conditions and disease. By 1987, 93% of East German Shepherds were free of hip dysplasia — a significant achievement compared to West Germany, where fewer than half were unaffected. The SZG Deutsche Schäferhunde registered over 170,000 dogs in its pedigree book until German reunification in 1990.

Postwar anti-German sentiment reduced foreign interest in the breed, particularly in the UK and US. The breed recovered in the 1950s. Von Stephanitz’s successors continued his work. The modern history of the German Shepherd is often considered to start with the 1951 German Championship and the success of Rolf vom Osnabrücker Land, a highly typified dog showing morphological innovations, notably in strength, neck, and shoulders, marking a step forward for the breed. Judge Walter Trox described him: “A powerful, well-built male, medium size, elongated and well-shaped body, with a strong, expressive head. His gait showed excellent endurance. He was presented at his best form. A high-quality stallion, already producing several 'Excellent' and 'Very Good' offspring.”

In 1955, Dr. Werner Funk, respected judge and breeder, became head of the SV (member since 1923). In France, Marcel Olive succeeded Georges Barais as head of SCBA, and the first main breeding exhibition took place in 1958 in Vichy, gathering French breeding elites.

On January 1, 1961, the one-millionth German Shepherd was registered in the SZ. In 1964, the SV president awarded the exhibition winner title for the first time to a dog he had personally bred (Zibu vom Haus Schütting). From August 1966, all registered German Shepherds underwent hip X-rays to combat hip dysplasia. Correct hips received an A rating.

Another major event: the EU of German Shepherd Clubs (EUSV) was founded on May 16, 1968, uniting 11 nations to strengthen international cooperation and breed consistency.

Rolf Vom Osnabrücker Land, 1951 (SZ 640721) – Of 2,058 dogs selected in Germany in 1967, more than half shared his bloodline.

Dr. Funk died in 1971. Dr. Rummel succeeded him, overseeing the growing SV, which now had over 80,000 members. That year, the SV mandated tattoos for all German Shepherds born in Germany before pedigree registration. On September 9, 1974, for SV’s 75th anniversary, the WUSV (World Union of German Shepherd Associations) was created. The SV continued to play a central role in guiding the breed’s future. Rummel outlined objectives: “A unified breed standard, harmonization of breeding evaluation, clarification of breeding and training issues, care, and hereditary disease control.”

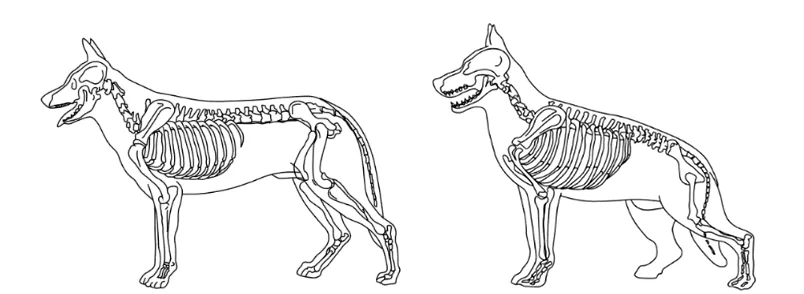

A second turning point in the 1970s was the emergence of the sloping topline, giving a lower stance, more ease, and endurance in trot. This was achieved through three complementary sires: Quanto von der Wienerau, Canto von der Wienerau, and Mutz von der Pelztierfarm. Their crossed offspring fixed the morphological characteristics of today’s German Shepherd.

Quanto von der Wienerau (SZ 1133695)

By the late 1970s, only descendants of these three sires remained, and in the mid-1980s, a new revolution occurred: two sons of Palme vom Wildsteiger Land, one of the most influential females in history, Uran vom Wilsteiger Land and Quando von Arminius, dominated the period and became the foundation of the modern breed. In France, Mabrouk, mascot of 30 Millions d’Amis, demonstrated courage and intelligence on television, shaping the public image of the brave, smart, loyal dog.

Palme vom Wildsteiger Land (SZ 1478659)

Quando von Arminius (SZ 1547134)

In 1982, Hermann Martin became SV president. In 1988, the European Championship was replaced by the WUSV World Championship, becoming a major international event. Over a century, the German Shepherd became one of the most popular breeds worldwide.

Peter Meßler succeeded H. Martin in 1994. In 1997, the SV registered the two-millionth German Shepherd in its studbook. Wolfgang Henke became president of the SV in 2002, followed by Heinrich Meßle in 2015 and Roswitha Dannenberg in 2023.

On January 1, 2011, the breed standard was revised with the official recognition of the long-haired German Shepherd by the FCI (Fédération Cynologique Internationale).

The breed’s original standard, first published in 1899, has undergone several revisions over the decades, mainly to clarify its wording and eliminate specific faults. The most striking difference between the dogs that conformed to the first standard and those of today unquestionably lies in the topline of the back. Max von Stephanitz was adamant on this point and regarded nothing but a straight back as ideal. However, over time, the breed standard evolved to describe a slightly sloping back. Today, the topline of show-line German Shepherds forms a continuous downward curve from the withers to the croup, a feature that becomes even more pronounced when the dogs are stacked for exhibition. The downward slope in show dogs has been criticized for reducing jumping ability, endurance, and agility, while working lines remain closer to the original functional form.

Despite the split between show and working lines, von Stephanitz’s legacy endures, and the German Shepherd remains one of the most popular breeds globally.

Photo Galleries, Pedigrees, and References:

- Champions 1899–2014

- Pedigree tracking

- Bibliography: A.Dupont, P.de Wailly, "Le Berger Allemand".

G.Teich Alasia, "Encyclopédie du Berger Allemand".

F.Fiorone, "Le Berger Allemand".

J.Ortega, "Le Berger Allemand".

Emmanuelle Francq, "Les origines des races européennes de chiens de berger".

D.Grandjean, F.Haymann, "Encyclopédie du Berger Allemand".

Resi Gerritsen, Ruud Haak, "The German Shepherd Dog".

Max von Stephanitz, "Der deutsche Schäferhund in Wort und Bild".