World War I

In 1914, the French Army, skeptical about the effectiveness of dogs on the battlefield, had only 250 military dogs, forcing the command to call upon civilian dogs. Citizens’ dogs were then requisitioned to “participate in the rescue of France.” An improvised kennel at the Jardin d’Acclimatation in Paris received dogs donated by the SPA and the Paris pound before their deployment to the front.

The use of military dogs became official in December 1915 with the creation of a war dog service within the infantry command. Germany, ahead in the use of military dogs, had 6,000 trained dogs at the start of hostilities. Of the 1,678 dogs sent to the front by the end of May 1915, 1,274 were German Shepherds.

Their roles were already diverse: patrol and sentinel dogs, medical dogs accompanying stretcher-bearers on the battlefield to locate the wounded, telegraph dogs carrying a spool of wire across dangerous trench paths to restore broken communication lines, messenger dogs carrying maps, ammunition, carrier pigeons, or sometimes simply cigarettes. From 1915 onward, following the first large-scale gas attacks, all dogs were trained to run wearing gas masks.

It is estimated that a total of 100,000 dogs were mobilized during the conflict: 30,000 on the German side, of which 7,000 reportedly perished, and 20,000 on the French side, of which 5,000 did not return. These numbers are only estimates, as records were not always kept or remain uncertain.

On November 21, 1918, a ministerial circular demobilized the war dogs. Veterans recounted numerous stories of their exploits. Among them, a soldier from Le Mans recalled: “Wounded by a shell fragment in my arm, a bullet in my jaw, and a sabre strike that had lifted my scalp, I was half-buried under the bodies of several comrades when I felt a touch on my forehead: it was a good medical dog licking my face. I managed to lift myself slightly despite my intense pain. I knew that dogs were trained to bring the caps of the wounded back to the camp, but mine was lost. The brave dog hesitated: ‘Go,’ I told him, ‘go my dog, go find the comrades.’ He understood me, ran flat out, and on returning to the camp he struggled so well, barking and tugging this one and that one by their coats, that he attracted the attention of two brave stretcher-bearers: they followed him, and he led them to me: I was saved.”

Some of these dogs were awarded decorations, and some became famous through touching stories and anecdotes. New enthusiasts discovered their countless qualities. The first German Shepherd guide dogs appeared to assist war-disabled and injured veterans.

In the aftermath of World War I, to erase all references to Germany, the breed was subsequently called the “Shepherd Dog” in the United States, the “Alsatian Wolf Dog” in the United Kingdom, and the “Berger d’Alsace” in France.

Departure of medical dogs from Asnières, 1915.

Medical dogs, German Army.

Telegraph dog laying out a communication line.

Wolf jumps here over a barbed wire fence on the Western Front in Flanders (Belgium).

Messenger dog of the German Army, 1916.

Collar of a medical dog and collar of a messenger dog, Germany 1914‑18.

In 2018, the Australian War Animal Memorials Association inaugurated in Pozières, in the Somme (France), a monument in memory of all animals that died during World War I.

World War II

During World War II, the German Shepherd was once again used at all levels and by armies around the world. Guard dogs, patrol dogs, liaison dogs, medical dogs, and even mine detection dogs continued to be widely employed.

When Hitler came to power, he created a central military dog training school in Kummersdorf. This cynotechnical center, then the largest in Europe, housed nearly 2,000 dogs. In 1939, upon the announcement of mobilization, the French army resumed military dog training, with the National Veterinary School of Alfort in charge of recruitment. Germany, which had been preparing for war for several years, already had 50,000 dogs.

As in the First World War, many dogs carried out remarkable actions. In July 1943, when a squad came under fire from an Italian machine gun nest, Chips, a German Shepherd-Husky cross assigned to the American army, charged alone at the enemy bunker. "The noise was terrible, then the firing stopped," recalls his owner John Rowell. "I then saw an Italian soldier emerge, grabbed by Chips by the throat. I called him back before he could kill him. And three other Italian soldiers appeared with their hands in the air." Chips had single-handedly forced their surrender.

Chips suffered minor burns during the battle but survived the war. In 1942, his family had given him to the American army in the name of the war effort. He returned to them but died in 1946 at six years old from kidney failure. In 1990, Disney released a TV movie based on his life, 'Chips, the War Dog.' He was posthumously awarded the PDSA Dickin Medal in 2018 and, in 2019, the Animals in War & Peace Medal of Valor, the American equivalent of the Dickin Medal.

On June 6, 1944, many dogs accompanied soldiers into combat during the Normandy landings, including Glen, a "Para Dog," and his handler Emile Corteil. They perished together on D-Day:

Medical dogs became, for the first time, disaster search dogs, looking for living or deceased victims in the ruins of London. Among them, Irma received the prestigious Dickin Medal, the equivalent of the Victoria Cross for a soldier, after refusing to stop her search in the rubble while the rescue team wanted to leave. Her perseverance saved two young girls still alive. Irma eventually found a total of 233 Blitz victims, including 21 still alive. Irma had the unique ability to indicate whether a person was alive or not based on how she barked. Jet of Iada is credited with saving 150 lives.

In 1941, the Red Army deployed anti-tank dogs against German armored vehicles:

The American army was already training and using dogs, mainly as sentries, and during the war mobilized over 10,000, sending 1,900 overseas.

1,074 dogs, called the "Devil Dogs," were enlisted by the Marine Corps during World War II. Most of the dogs were donated by families wanting to contribute to the war effort.

Used in combat in the dense jungles of the Pacific islands, their keen senses made them ideal for detecting ambushes. Others were enlisted to carry messages through the undergrowth, much faster and quieter than an American Marine exposed to enemy fire. Among them was Caesar von Steuben, a three-year-old German Shepherd, offered as a gesture of patriotism and civilian solidarity by his owners in New York. Caesar was already legendary in his Bronx neighborhood for delivering groceries and parcels.

Messenger dog training first involved desensitizing them to the chaos of battle and making them indifferent to explosions and gunfire. Then they were trained to carry messages over increasing distances and rougher terrain until a dog could easily pass from one handler to another over a kilometer of obstacles and dangers. During the war, messenger dogs became scout dogs.

Caesar repeatedly proved the invaluable role of a dog in war during his service. He landed with his handler at Bougainville on November 1, 1943. The next day, he made eleven runs, totaling 50 kilometers under fire between the patrol and the command post.

Two days later at dawn, the Japanese launched an attack on the Marines. Caesar heard the attackers before his handler and rushed out of their cover. When Mayo realized what was happening, he shouted for Caesar to return. But as the dog turned, he was hit by two bullets from a Japanese soldier. A firefight ensued, and the wounded Caesar reached the command post, alerting them to how close the enemy was.

His condition worsened. On a hastily set up field hospital bed, the veterinarian removed one bullet from his hip; the second, lodged near his heart, was "too risky to remove," he said while treating Caesar's wounds. It was close, but three weeks later, the Marine favorite of the Raiders was back in active service. He was the first dog wounded in the Pacific War.

War correspondents reported the extraordinary deeds of these dogs, making headlines: "Caesar helps take Bougainville," read the New Orleans Times-Picayune, noting that no patrol with a dog had lost a man.

Caesar later fought at Guam and then northern Okinawa, where on April 17, 1945, this large German Shepherd, still carrying his bullet near the heart, was killed in action.

After Japan's surrender, the surviving dogs returned to the Marine Base at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina. Half of the 1,074 enlisted Marine Corps dogs took part in combat. Fifty-eight died, 29 in action, including 25 at Guam, where a memorial now honors them at the U.S. naval base, and 5 went missing. Hundreds of dogs suffered from infections, parasites, malnutrition, and dehydration, and the noise of explosions heavily affected their mental health. 128 dogs were euthanized. However, a demobilization program was highly successful at the end of the war, allowing 491 Devil Dogs to return home. Handlers who had formed strong bonds with their dogs were allowed to adopt them.

Each unit often had its own mascot dog, adopted in the field or brought from the home country.

Germany used the most dogs during the conflict, deploying nearly 200,000. France used only a few hundred, convinced that mechanization and modernization of armies made dogs unnecessary. By the end of World War II, the toll was heavy, with tens of thousands of dogs having given their lives. The lack of precise figures is due to the destruction of military records, destroyed either by troops or archivists who saw no value in keeping them.

German soldiers and their messenger dogs.

The Devil Dogs and their handlers await orders on Bougainville. Caesar is on the right with his handler, Private First Class Rufus G. Mayo, 1943.

Messenger dog collars, USA 39-45.

Chips meets General Eisenhower, 1945.

Two American Marines kneeling alongside their German Shepherd, Battle of Iwo Jima 1945.

Irma receiving the Dickin Medal, January 12, 1945.

Indochina War

From 1948, war dogs were used by the French Expeditionary Corps in Indochina. They were employed either as guard and patrol dogs at sensitive points, or as patrol dogs. The former carried out daily, often unseen but effective work in ammunition and equipment depots, fuel depots, and airfields. The latter saved many human lives, often at the cost of their own.

The Indochina War marked a major first in the history of military dogs with the creation of the first parachute dog unit. Six German Shepherds aged 2 to 3 years — Borris, Cilly, Kado, Liedo, Lux, and Remo — became the first parachute canine combatants of the French army. These dogs, dropped from the sky, could perform missions such as mine detection, surveillance, searching, and tracking. This flawless efficiency would later be adopted by the U.S. Army under similar conditions.

The dog was parachuted alone and sometimes landed far from its handler.

The dog was parachuted alone and sometimes landed far from its handler.

Today, dogs are parachuted harnessed to their handlers.

Korean War

After World War II, the U.S. Army closed its dog training centers, leaving only the 26th ISDP (Infantry Scout Dog Platoon) active, tasked with demonstrating military dogs’ capabilities to the American public at events across the country. When the regiment landed in Korea in July 1950, there were only seven handlers and dogs; by the end of the war, 1,500 had participated in the conflict. These American Army scout dogs saved hundreds of GIs during the three-year war.

Their missions were simple but dangerous: ensuring that the scout dogs silently alerted the presence of the enemy during patrols. A post-war report stated that these patrols reduced casualties by 65%.

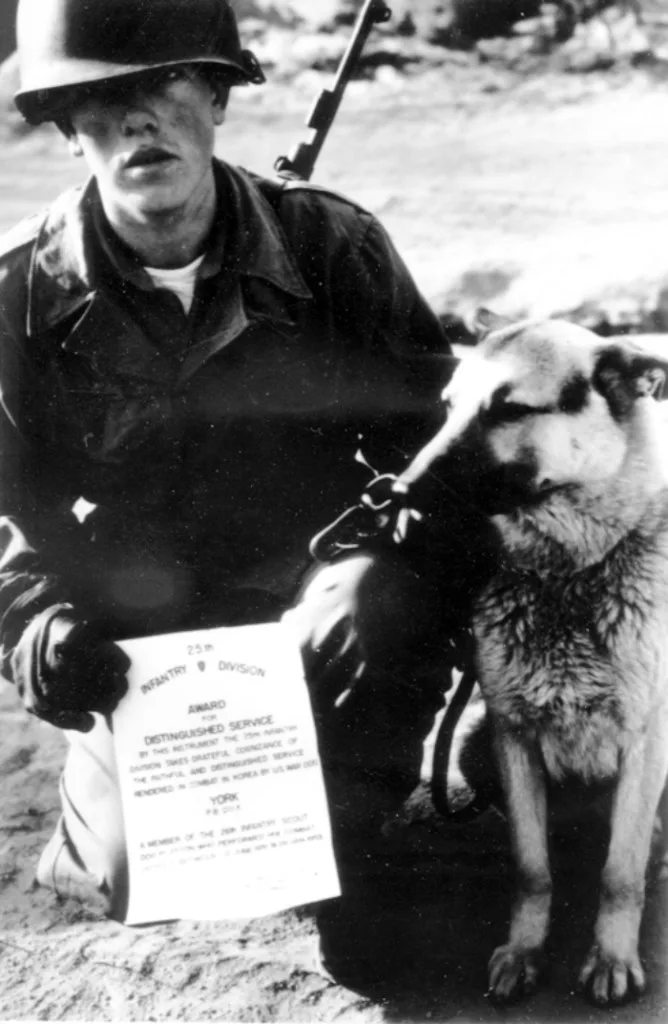

York (Serial 011X), an 8-year-old German Shepherd, was awarded for his exceptional service. He led 148 combat patrols without losing a single man. After the war, he returned to Fort Benning and was buried with honors at the age of 12.

At the end of the war, scout dogs not assigned to infantry divisions became sentry dogs in the Demilitarized Zone between North and South Korea.

Scout dog on patrol.

James Partain and his dog York receiving his citation.

War Dog Memorial (Colorado Springs).

Cold War

The Cold War between the Western and Eastern blocs gradually developed after World War II. In 1961, the Berlin Wall was erected, and thousands of German Shepherds from East Germany were deployed to guard this impassable border.

Algerian War

During the Algerian War, more than 7,000 dogs were used by the French Army, mainly purchased from Germany. They were assigned to 99 canine platoons.

These included guard dogs protecting military installations, mine-detection dogs that drastically reduced sabotage on railway lines, scout dogs leading combat units through rough terrain and brush to avoid ambushes, and tracking dogs trained to locate fighters of the National Liberation Front (FLN) who often hid in caves.

The most famous of these dogs was Gamin, a German Shepherd from the Beni-Messous military kennel whom no one could approach except his handler, Gendarme Gilbert Godefroid. In March 1958, during a law enforcement operation in the Barral region, handler Godefroid and Gamin went ahead alone. After five hours of tracking in extremely difficult terrain, the insurgents’ trail was found, but as Godefroid released his dog, a burst of gunfire mortally wounded the gendarme. Gamin, though seriously hit by a bullet in the head and one in the chest, leapt and killed his attacker. He then crawled to his master and lay over him for protection. It took six men and a tent canvas to restrain him. Brought back to base camp, he survived but no one could approach him again or give him orders.

On December 27, 1958, at the Beni-Messous kennel, a ceremonial guard was formed under Lieutenant Colonel Arcouet. Gamin became the first dog to be awarded the National Gendarmerie Medal. The military hierarchy decided to retire him to the Gramat (46) kennel, where, according to the ministry’s note, he would "receive attentive care until his death."

Gamin passed away on March 16, 1962. His ashes were placed at the heart of a stele at CNICG, commemorating both a man and a dog who became a model of loyalty and courage.

In July 2005, on the 60th anniversary of CNICG, Gamin’s ashes were symbolically transferred to the memory garden created at the school. In front of this stele in the memory garden, topped with a dog’s head made from horseshoes, the traditional ceremony for forming canine teams is held at each training course.

Search operations in the Aurès region.

Gilbert Godefroid and his dog Gamin.

Memory Garden, National Canine Instruction Center of the Gendarmerie.

Vietnam War

Many German Shepherds were again mobilized during the Vietnam War. Over 4,000 war dogs were deployed by the U.S. Army from 1965 to 1973. Thanks to their exceptional hearing and sense of smell, these dogs are credited with saving more than 10,000 American lives through their roles as guard dogs, scouts, and explosive detection dogs. Their effectiveness made them prime targets for the enemy, who attacked kennels and offered bounties for a dog’s tattooed ear or a handler’s shoulder patch.

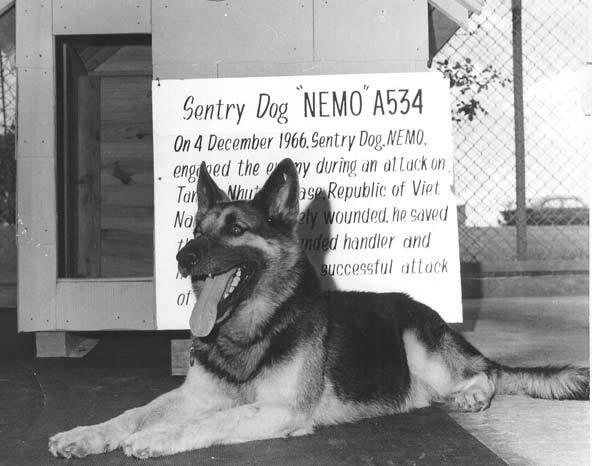

Once again, the war dogs demonstrated their prowess. Nemo, a German Shepherd paired with his handler, aviator Bob Thornburg, is a prime example. In 1966, during a patrol near a Vietnamese cemetery close to their airbase, Nemo suddenly became alert. But it was too late to react: the duo came under fire from the graves. A bullet pierced Thornburg’s shoulder, while another hit Nemo in the head, entering under his right eye and exiting through his mouth. Despite his severe injury, the 40-kilogram dog attacked the assailants fiercely, giving his handler time to call for backup.

Nemo then returned to his unconscious partner and, bleeding heavily, lay over him to shield him until help arrived.

Both were rescued, and the veterinarian managed to save Nemo’s life, although he lost his right eye.

On July 22, 1967, Nemo was transferred to the United States and returned to civilian life, becoming the first American dog from the Vietnam campaign to receive this honor.

Captain R.M. Sullivan, responsible for the detection dog program, took Nemo in. Together, they participated in numerous troop-support events until Nemo’s death in December 1972.

During troop withdrawals, many handlers who had formed strong bonds with their dogs wished to bring them home, but only a few were able to return to the U.S. The Department of Defense had classified thousands of these dogs as surplus equipment to be left behind. They were either euthanized by the U.S. Army or handed over to the South Vietnamese Army, facing grim fates. About 2,700 war dogs were transferred to the South Vietnamese Army, just over 300 were killed in combat, 1,300 were euthanized or abandoned, and 200 left Vietnam. It is estimated that they saved 10,000 lives during the war.

The Vietnam Dog Handler Association was created to help veterans cope with the guilt of leaving their dogs behind. Some developed post-traumatic stress disorder directly linked to these losses. "It was like leaving your child behind," recalls Fred Dorr, the association’s president. This ignoble ending motivated Vietnam war dog handlers to take action. Thanks largely to their collective efforts, the “Robby Law” was passed by the U.S. Congress and signed by President Clinton in 2000, ending the euthanasia of dogs at the end of their military service. The law also authorized the establishment of memorials honoring dogs killed in action. However, it remained extremely difficult for handlers to bring their dogs to the U.S. It was only in 2015 that Congress and President Obama signed legislation allowing military dogs to retire in the United States. They were first offered to their former handlers, then to law enforcement personnel, and finally to rigorously vetted families.

On September 28, 2019, the Motts Military Museum in Ohio inaugurated a memorial dedicated to these dogs and their handlers. On three black granite panels are inscribed the names of 4,244 dogs that served during the war and 297 names of handlers and veterinarians who died in Vietnam. The center panel displays the words "The Unbreakable Bond."

A soldier and his scout dog, South Vietnam 1966.

Sentry dogs and their handlers, Da Nang 1969.

Nemo, military ID A534.

Motts Military Museum Memorial.

War in Afghanistan

In Afghanistan, dogs were primarily used for detecting explosives and any chemical substances used to make improvised explosive devices.

In April 2016, Lucca made international headlines by receiving the Dickin Medal in London. She was the first female dog of the U.S. Marine Corps to receive this honor. During her six years of service, Lucca successfully completed 400 missions in Iraq and Afghanistan, protecting the lives of thousands of soldiers. None of them ever lost their lives while she was on duty.

During her last patrol on March 23, 2012, an IED exploded beneath Lucca, resulting in the loss of her leg. Corporal Rodriguez recalls, "The explosion was massive, and I immediately feared the worst for Lucca, but I saw her struggling to get up. I picked her up and ran to safety before applying a tourniquet to her injured leg. I stayed with her constantly throughout her surgery and recovery. She had saved my life on so many occasions; I had to be there for her when she needed me."

Lucca was airlifted to Germany for treatment, and ten days after the explosion, she was walking again. She then officially retired with the handler who had been her first partner for four years, Sergeant Chris Willingham. He said, "Lucca is very intelligent and loyal; her motivation for working as a detection dog was incredible. She is the only reason I returned home to my family, and I was lucky to serve with her. Today, I do my best to spoil her during her well-earned retirement."

In 2015, her life story was published in the book Top Dog: The Story of Marine Hero Lucca. She passed away on January 20, 2018, at the age of 14. She posthumously received the Animals in War & Peace Bravery Medal in November 2019. In July 2021, her ashes were transferred to the Michigan War Dog Memorial, where a ceremony was held in her honor.

Lucca poses with her Dickin Medal.

When a war ends, humans count their dead and shake hands. Animals, loyal companions and innocent victims of human folly, are often forgotten. Long absent from commemorations, war animals are finally receiving the recognition they deserve. Monuments erected in their honor remind us of their loyalty, bravery, and the heavy price they paid fighting alongside humans.

Today, dogs are still used in armed conflicts. In addition to performing their missions, they provide moral support to soldiers deployed in war zones for months or even years away from their families. Through numerous stories, poignant testimonies, and rare photos, explore the world of these four-legged soldiers in the darkest moments of war.

📖 The German Shepherd War Dog

Its history in conflicts from World War I to the present day.

From the mud of the trenches to courage on the battlefield, these dogs wrote their own legend.

Be captivated by the true stories of these hero dogs!